Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

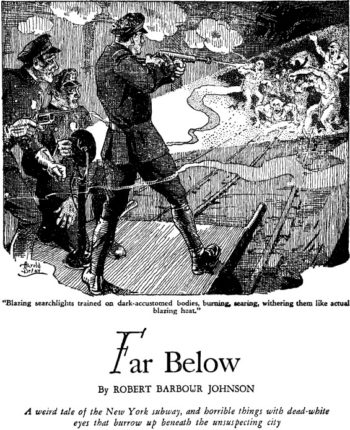

This week, we’re reading Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below,” first published in the June/July 1939 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

With a roar and a howl the thing was upon us, out of total darkness. Involuntarily I drew back as its headlights passed and every object in the little room rattled from the reverberations. Then the power-car was by, and there was only the ‘klackety-klack, klackety-klack’ of wheels and lighted windows flickering past like bits of film on a badly connected projection machine.

Summary

Our narrator visits the workplace of his friend Professor Gordon Craig. It’s Inspector Gordon Craig nowadays—it’s been twenty-five years since Craig left the New York Natural History Museum to head a special police detail stationed in a five-mile stretch of subway. The room’s crowded with switches and coils and curious mechanisms “and, dominating all, that great black board on which a luminous worm seemed to crawl.” The “worm” is Train Three-One, the last to pass through until dawn. Sensors and microphones along the tunnel record its passage—and anything else that might travel through.

The system’s expensive, but no one protested after the subway wreck that occurred just before America entered WWI. Authorities blamed the wreck on German spies. The public would have rioted if they’d known the truth!

In the eerie silence following the train’s roar, Craig goes on. Yes, the public would go mad if they knew what the officers experience. They stay sane by “never quite [defining] the thing in [their] own minds, objectively.” They never refer to the things by name, just as “Them.” Luckily, they don’t venture beyond this five-mile stretch. No one knows why they limit their range. Craig thinks they prefer the tunnel’s exceptional depth.

The subway wreck was no accident, see. They pulled up ties to derail the train, then swarmed on the dead and wounded passengers. Darkness kept survivors from seeing them, though it was bad enough to hear inhuman gibbering and feel claws raking their faces. One poor soul had an arm half-gnawed off, but the doctors amputated while he was unconscious and told him it was mangled by the wreck. First responders found one of them trapped in the wreckage. How it screamed under their lights. The lights themselves killed it, for Craig’s dissection proved its injuries minimal.

The authorities enlisted him as an ape expert. However, the creature was no ape. He officially described it as a “giant carrion-feeding, subterranean mole,” but the “canine and simian development of members” and its “startlingly humanoid cranial development” marked it as something more monstrous still. Only the huge salary made Craig accept a permanent position. That, and the opportunity to study an undocumented creature!

Not entirely undocumented, though, for didn’t the Bible reference “ghouls that burrow in the earth?” Manhattan’s native inhabitants took special precautions to guard their burials. Dutch and English settlers ran night patrols near cemeteries, and dug hasty graves for things unfit to be seen in daylight. Modern writers, too, hint at them. Take Lovecraft—where do you suppose he got “authentic” details?

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Craig’s not studied the creatures alive, too. Captives are useful for convincing incredulous authorities to approve the Detail’s work. But Craig can’t keep live specimens for long. They exude an intolerable “cosmic horror” that humans can’t live with in “the same sane world.” Detail officers have gone mad. One escaped into the tunnels, and it took weeks to corner and gun him down, for he was too far gone to save.

On the board a light flickers at 79th Street. A handcar speeds by, carrying armed officers. A radio amplifier emits “a strange high tittering,” growls, moans. It’s their chatter. No worry, the handcar will meet another coming from the opposite direction and trap the creatures between them. Listen, hear their howling, scrabbling flight. They won’t have time to “burrow down into their saving Mother Earth like the vermin they are.” Now they shriek as the officers’ lights sear them! Now machine guns rattle, and the things are dead. Dead! DEAD.

Narrator’s shocked to see how Craig’s eyes blaze, how he crouches with teeth bared. Why hasn’t he noticed before how long his friend’s jaw has become, how flattened his cranium?

Lapsing into despair, Craig drops into a chair. He’s felt the change. It happens to all Detail officers. They start staying underground, shy of daylight. Charnel desires blast their souls. Finally they run mad in the tunnel, to be shot down like dogs.

Even knowing his fate, Craig takes scientific interest in their origin. He believes they began as some anthropoid race older than Piltdown man. Modern humans drove them underground, where they “retrograded” in “the worm-haunted darkness.” Mere contact makes Craig and his men “retrograde” as well.

A train roars by, the Four-Fifteen Express. It’s sunrise on the surface, and people travel again, “unsuspecting of how they were safeguarded… but at what a cost!” For there can be no dawn for the guardians underground. No dawn “for poor lost souls down here in the eternal dark, far, far below.”

What’s Cyclopean: What isn’t cyclopean? The stygian depths of the subway tunnels, beneath the crepuscular earth, are full of fungoid moisture and miasmic darkness and charnel horrors.

The Degenerate Dutch: Native Americans ostensibly sold Manhattan to white people because it was so ghoul-infested. Though they managed to live with the ghouls without exterminating them—it’s only the “civilized” who find them so revolting that they have to carry out “pogroms” with a ruthlessness born of “soul-shuddering detestation.”

Mythos Making: Gordon Craig learned something from Lovecraft—the name Nyarlathotep, if nothing else—and vice versa, though Lovecraft toned it down for the masses.

Libronomicon: You can find ghouls described in the writings of Jan Van der Rhees, Woulter Van Twiller, and Washington Irving, as well as in “The History of the City of New York.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: People would go mad if they knew what was down here in the subway tunnels. And it seems like many who know do go mad. Though given the number of people who know, that might just be probability.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

When I was a kid, I made it to New York once a year, to visit my grandmother in Queens. The rest of the year I lived on Cape Cod, a beautiful seaside community almost entirely free of public transit. I loved—and still love—the subway fiercely, as one would love any magic portal that allows one to travel between destinations simply by stepping through a door and waiting. But I also knew without question that it was otherworldly. The saurian cry of a train coming into the station, the cyberpunk scent of metal and trash wafting from the tracks—I understood well that not everything down there was human or safe, and not every station was on the map.

Lovecraft was famously afraid of the ocean, a medium that humans have plied for millennia even though it can kill us in a moment. But the world beneath the earth’s surface is even less our natural environment, and it’s only in the last century that we’ve traveled there regularly. The New York subway system opened in 1904, a little taste of those mysteries for anyone who used it.

Johnson gives us a mystery—in the old sense, something that people go into a hidden space to experience, and then don’t talk about. Something transformative. But in this case, the transformation and the silence seem less sacred and more a combination of inhumanly horrifying—and humanly horrifying. A gut-churning episode of 99% Invisible talks about how doctors came around to the idea that you should tell people when they had a fatal illness, and how before that they would pretend that the person was going to be fine, and all their relatives had to pretend the same thing, and if the patient figured it out then they had to pretend they believed the lies… speaking of nightmares. If a ghoul had eaten my arm, I’d want to know, and I’d probably want to tell someone.

The (post-war?) cultural agreement to Not Talk About It seems to have gone on for a while, and is certainly reflected in Lovecraft’s desperate-to-talk narrators who, nevertheless, urge the listener to tell no one lest civilization collapse from the correlation of its contents. You can’t tell people bad things, because obviously they can’t handle it. Everyone knows that.

And everyone knows about the ghouls, and no one talks about them. The entire city administration, the relatives who sign off on shooting their transformed family members, doctors who amputate gnawed limbs, all the writers of histories in all the nations of the world… but if they were forced to admit they knew, it would all fall apart.

I spent much of the story wondering whether Johnson was truly conscious of the all-too-human horror in his story. “We filled out full Departmental reports, and got the consent of his relatives, and so on” seems to echo the full-fledged bloodthirsty bureaucracy of Nazi Germany. And “pogroms” isn’t normally a word to be used approvingly. The ending suggests—I hope, I think—that these echoes are deliberate, despite the places where (as the editors say) the story “ages badly.”

I wonder how many readers got it, and how many nodded along as easily as they did to Lovecraft’s entirely un-self-conscious suggestion that there are some things so cosmically horrible that you can’t help attacking them. Even when it’s “no longer warfare.” Even when the Things are howling with terror, shrieking in agony. Some things just need to die, right? Everyone knows that.

And then another awkward question: To what degree is Craig’s xenophobia—his glee at destroying things with “brain convolutions indicating a degree of intelligence that…”—a symptom of his transformation? Which is also to say, to what degree is it conveniently a ghoulish thing, and to what degree is it a human thing? Or more accurately, given how many human cultures have lived alongside (aboveside?) ghouls with far less conflict, to what degree is it a “civilization” thing? For Lovecraftian definitions of civilization, of course.

Anne’s Commentary

Things live underground; we all know this. Fungi, earthworms, grubs, ants, moles, naked mole rats, prairie dogs, trapdoor spiders, fossorial snakes, blind cave fish and bats and star-mimicking glowworms, not to mention all the soil bacteria, though they richly deserve mentioning. It’s cozy underground, away from the vagaries of weather. Plus it’s a good strategy for avoiding surface predators, including we humans. The strategy’s not foolproof. Humans may not have strong claws for digging, but they can invent stuff like shovels and backhoes and, wait for it, subways!

Subways, like cellars and mines and sewers, are human-made caves. Some are cozy, say your finished basements. Others, like their natural counterparts, are inherently scary. They’re dark, and claustrophobic, and (see above) things live in them. Pale things. Blind things. Squirmy, slimy things. Disease-carrying things. Things that might like to eat us. Things that inevitably will eat us, if we’re buried underground after death.

It’s no wonder ghouls are among the most enduring monsters in our imaginations. Robert Barbour Johnson’s are quintessential ghouls, closely akin to Lovecraft’s Bostonian underdwellers, on whom they’re based. One of Pickman’s most terrifying paintings is his “Subway Accident,” in which he imagines ghouls rampaging among the commuters on a boarding platform. Or did Pickman only imagine it? Could Boston have suffered a calamity like the one in Johnson’s New York—and one as successfully covered up? If so, Pickman would have known about it, for his ghoul friends would have bragged about the incident.

Johnson’s father worked as an undercover railroad policeman, family background that made Johnson a natural to write “Far Below.” It’s the most famous of the six pieces he published in Weird Tales; in 1953, readers voted it the best of the magazine’s stories, ever. That’s saying a hell of a lot for its popularity, considering it beat the likes of Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, C. L. Moore, Robert Bloch and, of course, our Howard himself. Lovecraft admired Johnson’s work. In “Far Below,” Johnson returned the compliment by name-checking Lovecraft in the time-honored manner of claiming him as a scholar of factual horrors, thinly disguised as fiction.

Johnson’s tribute to “Pickman’s Model” extends to the form of “Far Below” in that it’s largely an account given by a ghoul-traumatized man to a friend. It adds more present-moment action in that the listening friend personally witnesses ghoul activity and then realizes his friend is himself “retrograding” to ghoulishness. It adds horror for narrator and reader in that narrator can’t write off Craig as delusional. It adds terror in that if Craig is “ghoulizing” by spiritual contagion from them, might not narrator catch at least a mild case of “ghoul” from Craig?

Craig may delude himself by theorizing ghouls originated in a “lesser” ancestor of mankind—Homo sapiens, such as himself, are obviously not immune to the “retrograde” tendency. Irony compounds because Homo sapiens may have created ghouls by driving their progenitor species underground. H.G. Wells dished up similar irony in The Time Machine, imagining future humans who’ve differentiated into two races. Elites drove underclass workers actually underground, where they “devolved” into the cannibalistic (ghoul-like) Morlocks who prey on the privilege-weakened elite or Eloi. I also recall the 1984 movie C.H.U.D., which stands for Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers. See, the homeless were driven into the sewers, where they encountered hazardous chemical waste cached in the tunnels. The homeless people mutated into (ghoul-like) monsters who emerged to eat their former species-mates, that is, us. Our fault, for (1) allowing homelessness, and (2) countenancing illegal dumping.

Lovecraft, on the other hand, doesn’t blame humanity for the ghouls. In the Dreamlands, they’re just part of the weird ecosystem. In the waking world, ghouls and humanity are clearly related species, with intermixing a possibility. “Pickman’s Model” narrator Thurber has an affinity for the macabre strong enough to have drawn him to Pickman’s art but too weak to embrace the reality of the nightside—he’s vehemently anti-ghoul. Johnson’s internal narrator Craig is more complex. At first he presents as gung-ho anti-ghoul, a proper bulwark between bad them and good us. As the story advances, he subtly evinces sympathy for the ghouls. The Inspector protests too much, I think, in describing how devilish they are, what spawn of hell! When relating the capture and killing of ghouls, he dwells on their agonies with surface relish and underlying empathy, and why not? Due to the spiritual “taint” that increasingly ties Craig to them, are not the ghouls more and more his kin? In his theory of their origin, does he not portray them as the victims of fire and steel, pogrom and genocide?

Poor Craig, his acceptance of impending ghoulhood is tortured. He’ll go into the tunnels only to be gunned down. What a contrast to Lovecraft’s Pickman, who seems to anticipate his transformation with glee. What a contrast to Lovecraft’s Innsmouth narrator, who anticipates outright glory in metamorphosis.

I guess it makes sense. Most of us would have reservations about living in subway tunnels, especially the dankest, darkest, deepest ones. Whereas Y’ha-nthlei far below sounds like an undersea resort of the highest quality.

Can I make a reservation for the Big Y, please? Not that I wouldn’t visit the tunnels with the ghouls, provided you could get rid of those pesky humans with overpowered flashlights and machine guns.

Next week, we go back about ground but still hide from the light with Autumn Christian’s “Shadow Machine.” You can find it in Ashes and Entropy.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.